Electronic Cigarette Use and Risk of Lung Injury

Electronic cigarette use has increased rapidly. Although vaping may aid with stopping cigarette smoking, cases of severe pulmonary disease and several deaths related to vaping have been reported.

AUTHORS

Frank LoVecchio, DO, MPH, Creighton and University of Arizona College of Medicine, Arizona State University, College of Health Solutions, Valleywise Health Medical Center, AZ

Laila LoVecchio, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

PEER REVIEWER

Glen D. Solomon, MD, FACP, Professor and Chair, Department of Internal Medicine, Wright State University Boonshoft School

of Medicine, Dayton, OH

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted the association of vaping and acute respiratory distress syndrome. As of February 2020, there have been almost 3,000 cases, including 68 deaths. Although the number of new cases has decreased, new cases are still appearing.

- Although most of the vaping material from patients with e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury contains tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), it appears that the causative agent is vitamin E acetate, used as a diluent for THC. While vitamin E acetate is benign when ingested, it is a lipid that when heated and inhaled can cause an inflammatory reaction.

- Although many individuals can vape without incident, some, particularly those who receive their product from overseas, can develop acute respiratory distress syndrome. This presents with hypoxia and ground glass infiltrates on chest X-ray, chest computed tomography, or chest ultrasound. Many patients require mechanical ventilation with standard acute respiratory distress syndrome protocols. Some patients have been successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use has increased rapidly. Although vaping may aid with stopping cigarette smoking, cases of severe pulmonary disease and several deaths related to vaping have been reported. Nicotine vaping by adolescents continued to increase from 2018 to 2019. This is the largest increase for any substance tracked by Monitoring the Future during the past 44 years.1 In addition, online surveys suggest cannabis vaping among adolescent cannabis users is increasing. In states where marijuana dispensaries are legal, lifetime vaping has increased threefold, and edible marijuana product use has increased 330%.2,3 In states that permit home growing of marijuana, the lifetime risk of vaping and edible use by residents has increased, and it is up to three times higher than in regions where growing marijuana plants for consumption is not allowed.4

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), state and local health departments, and other clinical and public health partners investigated a multistate outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products.

Epidemiology of the Outbreak

As of Feb. 18, 2020, there were 2,807 cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) reported to the CDC. This number is a moving target; unfortunately, it still is increasing almost daily. The CDC website is updated frequently and includes information for practitioners as well as the general public (www.cdc.gov). This website includes daily counts, patient identification and treatment recommendations, and discharge instructions for those who vape. These discharge instructions are available for distribution to all patients who vape or who have signs and symptoms of potential toxicity.2-4

Also, as of Feb. 18, 2020, 68 deaths have been confirmed. Most of these deaths, and most of the cases, occurred early in the outbreak. Yet, there is continued disease, particularly among adolescents. Most of the deaths are related to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)-like syndromes.

History of Vaping

Despite the recent epidemic, vaping has been present for decades. The fact that it has been around for so long suggests that a recent additive has resulted in EVALI. Although e-cigarettes are a modern trend, people in ancient Egypt used hot stones to vape herbs. Even thousands of years ago, the first shisha was used in India.

E-cigarettes were invented in 1927, and a vaping instrument was patented in 1965. However, in the 1990s, the FDA blocked tobacco companies from introducing e-cigarettes to the market, but eventually lost the battle.5

The first e-cigarette appeared in the United States in 2007. Two brothers from the United Kingdom are credited with inventing the cartomizer. A cartomizer connects directly to the battery and heats the electronic cigarette liquid, typically nicotine or tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

Cartomizers heat the liquid until it creates vapor, just like an atomizer. The heating coil in the cartomizer allows a longer time of vaping compared to atomizers.

The first death from an electronic cigarette is thought to have occurred in May 2018 in Florida.6 The man experienced burns on 80% of his body, and at least two parts of the exploding vape pen were removed from his cranium.

However, exploding vape pens are very rare. Most vaping pens have safety features to ensure the devices do not overheat, thus minimizing the explosion risk.

Patient Exposure

Before the current epidemic, pulmonary disease related to vaping was noted in sporadic case reports. In most of the cases, the disease was related to mechanical injury (spontaneous pneumothorax), pneumonia, or eosinophilic and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. The recent lung injury patients have reported a history of using e-cigarette, or vaping, products.7,8 The evidence for the actual cause is largely circumstantial, based on data that are retrospective.

However, well-done prospective trials are unlikely and unethical at this point. Most experts now believe that vitamin E acetate, which often is added to THC, is responsible for EVALI.

Most of the patients with EVALI have used products that contain THC. THC is the psychoactive, mind-altering compound of marijuana that produces the “high” or desired effect and would be possible to “vape” without additives. THC stimulates cells in the brain to release dopamine, creating euphoria. It also interferes with information processing in the hippocampus, which is partially responsible for forming new memories.

Almost all the patients with EVALI reported using THC-containing products that were obtained from poorly controlled sources, or THC- and nicotine-containing products. The vaping liquid can contain nicotine, THC, and cannabinoid (CBD) oils, as well as other substances and additives. In general, the industry is poorly controlled, and accurate labeling is scarce. The additives typically are used to increase the volume or to prevent the liquid from freezing.

The latest information suggests that products containing THC, especially those obtained off the street or from other informal sources (e.g., friends, family members, or illicit dealers), are linked to most of the cases and have a major role in the outbreak.

THC is present in most of the samples tested by the FDA associated with EVALI. Most of these products have been purchased in bulk, and a diluent has been added. One hypothesis is that counterfeit, low-cost, THC-containing cartridges with diluents that are not well tested contributed to the EVALI outbreak. Most manufacturers are unregulated abroad and in the United States. It is difficult to blame one specific brand for the same or similar products that are sold under multiple brand names. Currently, “Dank Vapes” brands have been used by many who have experienced vaping-induced lung injury (EVILI). Dank Vapes is not a single brand but represents wholesalers in China and is sold as multiple “brands.” Occasionally, these products contain pesticides, or they are combined with thickening agents, such as vitamin E acetate. Vitamin E acetate was identified in all of the Dank Vapes products linked to illnesses in New York state.9

Vitamin E acetate often is chosen as a diluent because its physical properties do not alter the taste of the substance, in this case THC or nicotine. Vitamin E acetate is safe when ingested, but, in part because of its lipid base, it is harmful if aspirated or inhaled into the lungs. Vitamin E acetate is cheap, and it mimics the characteristics of presumed safer and more expensive diluents. Similar to most chemicals, when heated, the chemical properties change. In this case, breakdown products might result in an inflammatory cascade that results in EVALI.

Another proposed mechanism is that heating and aerosolization followed by deposition into the lower airways results in the appearance of a lipoid pneumonia that appears on lavage fluid.

Classically, lipoid pneumonia is slow in onset and may take months to present clinically. A chronic cough often is a hallmark that is related to recurrent aspiration of oils. Therefore, although vitamin E acetate is lipoid, there may be other factors at work. There may be macrophage accumulation of lipids released after an injury to alveolar epithelial cells and not “true” or classic lipoid pneumonia.

The CDC announced on Nov. 21, 2019, that vitamin E acetate was “a chemical of concern” in patients with EVALI. The most convincing evidence was the presence of vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid samples (fluid samples collected from the lungs) from 29 patients with EVALI that were submitted to the CDC. Vitamin E acetate was present in all lung fluid.

Whether the EVALI culprit is only vitamin E acetate or a combination of pulmonary toxins is not clear. The FDA has reported that e-cigarette cartridges and solutions contain nitrosamines, diethylene glycol, and other contaminants that are potentially harmful to humans. Therefore, other substances may be playing a role, potentially setting up the process for vitamin E acetate accumulation.

Multiple additives cause oxidative stress on the lung epithelium, but the clinical significance is not well understood. Similar to smoking tobacco, the true results likely will not be known for many years.

In summary, most cases involve the use of an e-cigarette or similar product with THC and/or vitamin E acetate.

Other additives, including nicotine, cannabinoid oils, and other substances (such as limonene or coconut oil), also may play a role.

Patient Presentation

Although the most likely place for patients with EVALI to present is the emergency department (ED), primary care providers should be aware of this potentially life-threatening and preventable disorder.

Of the 1,378 patients for whom data on sex were available (as of Oct. 15, 2019), 70% were male.10 In the 1,364 patients with data available on age (as of Oct. 15, 2019), the median age was 24 years, and ages ranged from 13 to 75 years. Seventy-nine percent of patients were younger than 35 years of age. By age group category:

- 14% of patients were younger than 18 years of age;

- 40% of patients were 18 to 24 years of age;

- 25% of patients were 25 to 34 years of age; and

- 21% of patients were 35 years of age or older.10

Most of the cases of ARDS induced by vaping have involved a prodrome of upper respiratory complaints (not all patients could be interviewed). The prodrome of symptoms, such as cough and fever, mimic many diseases encountered by providers.

The history of the type of vaping product used may offer some useful clues to clinicians. In one study, of the 867 (54%) EVALI patients with available data on the use of specific products in the three months preceding symptom onset, 86% reported any use of products containing THC, 64% reported any use of products containing nicotine, and 52% reported using both.10 These findings could be subject to recall bias.

Data on the substances used in e-cigarette, or vaping, products were self-reported, and the history may be altered because nonmedical marijuana is illegal in many states.

In a case series, Kalininskiy et al retrospectively evaluated 12 patients with EVALI, which was defined as respiratory failure without another obvious cause and a history of e-cigarette or vaping use. In the ED, nine of 12 patients (75%) were hypoxic and eight of 12 (67%) were tachycardic. Most patients exhibited a fever (75%).11

Procalcitonin concentrations were elevated in eight (89%) of nine patients tested, with a median value of 0.99 ng/mL (0.36-2.70; normal range < 0.09). The median C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration was 232 mg/L (129-347; normal range 0-10). The initial median white blood cell count was 14,600 per microliter, and all patients generally had a neutrophil predominance. No eosinophilia was observed.11

Most patients who develop serious disease develop ARDS, which is an inflammatory reaction to a stimulus that causes diffuse lung injury. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are released in response to a stimulus, which can be sepsis, trauma, vaping, etc. The cytokines react locally with neutrophils to release toxic mediators, which damage the endothelium of capillaries, leading to the accumulation of protein and fluid in the alveolus. Patients present initially with shortness of breath.

Most patients (91%) presenting with suspected EVALI will have a chest radiograph that shows diffuse hazy or consolidative opacities. Bilateral opacities are typical in EVALI. In a series of 53 patients, bilateral opacities were noted in 100%, either on the chest radiograph or chest computed tomography (CT). The CT opacities typically were ground glass in density and sometimes spared the subpleural space. Pleural effusions were less common (approximately 10%). These features are consistent with diffuse alveolar damage, as is seen in ARDS.7

Currently, no radiographic finding is classic, and atypical findings are the most common. A chest CT is more sensitive and often will show more extensive disease.

In a case series of 11 patients with assumed EVALI, CT findings revealed bilateral ground glass opacification in all patients. A patchy ground glass opacification pattern and subpleural sparing were present in seven of the 11 patients (64%).

Ultrasound of the lung also can show disease; however, not all physicians are capable of performing and interpreting chest ultrasounds.

In general, if radiographs suggest EVALI, then further testing is warranted to rule out more common or similar diseases. In one series, in most patients (8/9 or 89%) who were tested, THC was identified on urine toxicological screen.11,12 Most laboratory studies are performed to ensure that the patient does not have another etiology for their symptoms. These tests include complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, electrocardiogram, liver enzymes, and sputum samples, if available.

In general, a CBC and inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP are recommended. A complete metabolic panel (CMP), urinalysis, and electrocardiogram should be considered. Testing for infectious disease should include blood cultures, a viral panel, influenza testing, mycoplasma testing, streptococcal pneumonia, Legionella, and HIV. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. Proposed Criteria for E-Cigarette or Vaping Induced Lung Injury (EVALI)

Confirmed case

- Use of an e-cigarette (“vaping”) or “dabbing” in the previous 90 days*

- Lung opacities on chest radiograph or computed tomography

- Exclusion of lung infection based on:

- Negative influenza PCR or rapid test (unless out of season)

- Negative respiratory viral panel

- Negative testing for clinically indicated respiratory infections (e.g., urine antigen test for Legionella and Streptococcus pneumoniae, blood cultures, sputum cultures if producing sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage, if performed)

- Negative testing for HIV-related opportunistic respiratory infections (if appropriate)

- Absence of a plausible alternative diagnosis (e.g., cardiac, neoplastic, rheumatologic)

Probable case

- Use of an e-cigarette (“vaping”) or “dabbing” in the previous 90 days*

- Lung opacities on chest radiograph (diffuse hazy or consolidative opacities) or computed tomography (ground glass or consolidative opacities)

- Infection identified through culture or PCR, but the clinical team believes this infection is not the sole cause of the underlying lung injury

OR

- Minimum criteria to rule out pulmonary infection not met (testing not performed) and clinical team believes infection is not the sole cause of the underlying lung injury

- Absence of a plausible alternative diagnosis (e.g., cardiac, neoplastic, rheumatologic)

* Using an electronic device (e.g., electronic nicotine delivery system [ENDS], electronic cigarette, e-cigarette, vaporizer, vape[s], vape pen, dab pen, or other device) or dabbing (e.g., nicotine, marijuana, THC, THC concentrates, CBD, synthetic cannabinoids, flavorings, or other substances). Dabbing refers to the use of a pipe to smoke substances (e.g., nicotine, THC) that have been concentrated into a wax.

EVALI: E-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury;

PCR: polymerase chain reaction; THC: tetrahydrocannabinol; CBD: cannabidiol.

Adapted from: Schier JG, Meiman JG, Layden J, et al. Severe pulmonary disease associated with electronic-cigarette-product use - Interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:787.

Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin - Final report. N Engl J Med 2019;382:903-916.

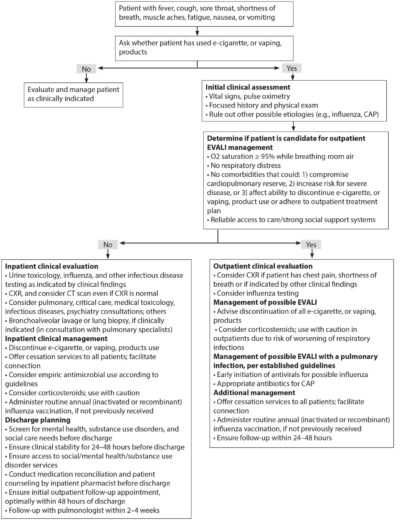

Treatment

Treatment for EVALI is supportive. There is no specific treatment for EVALI. The most important step is to ensure that other diseases, such as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) or pulmonary embolism, are excluded by the history, physical exam, or diagnostic data as indicated. (See Figure 1.) Treatment has ranged from supportive care to mechanical ventilation to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Ideal regimens and treatment have not been well studied.

Figure 1. Algorithm for Management of Patients with Respiratory, Gastrointestinal, or Constitutional Symptoms and E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Product Use (12/20/2019)

For the majority of patients with EVALI, empiric antibiotics are initiated to cover likely pathogens of CAP, pending the results of the initial evaluation and response to therapy. Although the mechanism is not believed to be of infectious origin, until further data are available, it seems prudent for emergency medicine providers to start antibiotics empirically that are used commonly for CAP.

Oxygen and respiratory support are administered as needed. Antivirals should be considered unless influenza A and B are excluded. Systemic glucocorticoids seem reasonable.

Corticosteroids have been used in a number of patients, but their effect is not clear. However, corticosteroids do not appear to cause harm for ARDS secondary to vaping, although they may cause harm in ARDS patients with other insults. Most cases have received a short steroid burst, starting with the equivalent of methylprednisolone 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg per day and over five to 10 days, guided by the clinical course.

Many patients will go on to require mechanical ventilation. Ventilation of patients with ARDS can be complicated, and an intensivist should be consulted early, if available. Patients will have a large shunt with ventilation/perfusion mismatch, decreased compliance (stiff lungs), and pulmonary hypertension. Barotrauma from mechanical ventilation and high pressures is a significant complication. Most intensive care units use a “lung sparing” approach, which uses lower tidal volumes with varying levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Patients who are not sufficiently ventilated on mechanical ventilation should be considered for ECMO.

After the patient is intubated, bronchial fluid is more available. Fluid obtained from a BAL should be sent to the CDC for analysis.

In addition, any vaping material (i.e., cartridges or loaded devices) should be sent to the CDC. The CDC website has information on how specimens can be sent. The CDC currently is testing BAL fluid samples, as well as blood or urine samples paired to BAL fluid samples. The CDC also is testing pathologic specimens, including lung biopsy or autopsy specimens, associated with patients suspected to have EVALI.

Differential Diagnosis

Various respiratory diseases are in the differential diagnosis of EVALI. All patients with suspected EVALI should undergo an evaluation for CAP, which is much more common. Besides CAP, ARDS and pulmonary embolism (PE) are potentially life-threatening diseases with possible interventions.

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) has a similar time course of symptom onset, and it typically is associated with BAL eosinophilia (> 25% eosinophils) and has been reported in association with vaping and the use of heat-not-burn cigarettes, as well as several other potential irritants and toxins.

Organizing pneumonia, a diffuse interstitial lung disease (ILD) that affects the distal bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, alveolar duct, and alveolar walls, has been reported in a few patients after using e-cigarettes.

Lipoid pneumonia is reported most commonly after aspiration of ingested mineral oil, but it also has been reported after vaping with products containing vegetable oil. CT findings of lipoid pneumonia typically include consolidative and ground glass opacities, interlobular septal thickening, and nodular or mass-like consolidation.

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage — dyspnea, hemoptysis, and hypoxemia — after about one month of frequent vaping with various flavors has been reported. CT revealed patchy areas of consolidation, and BAL revealed alveolar hemorrhage.

Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (RBILD) is associated with chronic inhalation of tobacco smoke. CT features of RBILD include diffuse or patchy ground glass opacities, centrilobular nodules, bronchial wall thickening, and air trapping.

Giant cell pneumonitis typically is associated with heavy metal exposure and has been considered in EVALI.6,12-14,16,17

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Findings

The most extensive review to date was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019. Researchers evaluated lung biopsies from 17 patients (13 men; median age, 35 years [range, 19-67 years]) with a history of vaping (71% with marijuana or cannabis oils) who were clinically suspected to have vaping-associated lung injury. The presentation was acute or subacute in all cases, with bilateral pulmonary opacities. All cases exhibited histopathological findings showing patterns of acute lung injury, including acute fibrinous pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar damage, or organizing pneumonia, usually bronchiolocentric, and bronchiolitis. No histologic findings were specific, but foamy macrophages and pneumocyte vacuolization were seen in all cases.8

Mortality

The median age of EVALI patients who died was 45 years, ranging from 17 to 75 years (as of Oct. 29, 2019). More deaths still are under investigation. The median age of patients with EVALI who survived was 23 years of age.10

Patient Disposition

Not all patients with EVALI will need to be admitted. Only those with hypoxia, chest infiltrates consistent with ARDS, or respiratory distress require admission. Since EVALI peaked in late 2019, more “worried well” who vape have been seen, concerned that they might be ill. Patients with no symptoms can be discharged.

Until more studies are done, it seems prudent to be conservative in patients with possible EVALI. Patients with EVALI who can be considered for outpatient management should have normal oxygen saturation (≥ 95% while breathing room air), no respiratory distress, no comorbidities that might compromise pulmonary reserve, reliable access to care, and strong social support systems. Patients also should be able to seek medical care quickly if respiratory symptoms worsen. In some cases, patients who had mild symptoms initially had symptoms worsen rapidly within 48 hours.2,3 Healthcare providers should consider obtaining a chest CT scan if patients have an initial normal chest X-ray but have symptoms and an exposure history suggestive of EVALI. Healthcare providers should advise all patients to refrain from vaping. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Assessing the Risk of Lung Injury in Patients Using E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products |

You should ask all patients about their use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. This is particularly important for patients with any of the following symptoms:

Ask with Empathy and Understanding Some patients may not be comfortable talking about their e-cigarette, or vaping, product use, especially those who use products that contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or cannabidiol (CBD). To put patients at ease, be empathetic, nonjudgmental, and remind them their responses are confidential and an important part of their medical exam. Adolescents and young adults are more likely to share sensitive information if you ask a parent/guardian to step outside the exam room. You may need to ask additional questions that are appropriate to each patient’s special situation or circumstances. Ask What, How, and Where What Ask the patient if they have used or tried e-cigarettes, or vaping, products. If the answer is yes, ask for more details about the products, including the types of substances used.

How Ask how often patients have used these products, and when they last used the products.

Where Ask where the e-cigarette, or vaping, products were obtained.

Resources For information on EVALI clinical guidance, please see www.cdc.gov/lunginjury. Guidance for assessing and treatment of EVALI is evolving and will continue to be updated as new evidence becomes available. Resources to help patients stop the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products can be found at https://smokefree.gov/. |

Adapted from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Don’t forget to ask: Assessing the risk of lung injury in patients using e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Dec. 9, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease/healthcare-providers/pdfs/dont-forget-to-ask-assessing-the-risk-of-lung-injury-508.pdf |

In addition to heavy metals, propylene glycol/glycerol is a common additive in vaping products. In a randomized study, acute vaping of propylene glycol/glycerol aerosol at high wattage, either with or without nicotine, induced airway epithelial injury and sustained decrement in transcutaneous oxygen tension in young tobacco smokers. Intense vaping conditions also transiently impaired arterial oxygen levels in heavy users. Oral ingestion of propylene glycol/glycerol in amounts higher than those achieved through e-cigarette inhalation is not associated with significant systemic toxicity. However, little is known about inhalation toxicity, and this study suggests local surface damage and decreased oxygen carrying. The long-term effects of vaping propylene glycol/glycerol remain unclear.18-20

While the long-term effects of EVALI are not known, follow-up evaluation clinically and radiologically to ensure resolution of the process is appropriate. Patients should refrain from future vaping.

In patients with addiction to products containing THC or nicotine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, contingency management, risk reduction, motivational enhancement therapy, pharmacological support, and multidimensional family therapy may help, but no one therapy is universally beneficial to all patients with addiction. Referral with addiction medicine services should be considered, if available.10,17,21-24

The CDC recommends that people should not use THC-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products, especially those from informal sources, such as friends, family members, or in-person or online dealers. Vitamin E acetate should not be added to e-cigarette or vaping products. Providers should warn patients about the potential danger of vaping, especially vaping THC-containing products.

People also should not add any substances to e-cigarette or vaping products that are not intended by the manufacturer, including any products purchased from retail establishments. The CDC will continue to update guidance, as appropriate, as new data become available from the outbreak investigation.

Prognosis

EVALI is a serious respiratory illness and there is likely a continuum of patients with less severe acute lung pathology. Most patients with EVALI require oxygen (~90%) and about one-third require intubation. As noted earlier, 68 deaths have been reported as of Feb. 18, 2020.

The long-term outcomes and subsequent use of vaping-related products have not been well reported. Case series among adolescents suggest residual airway reactivity or diffusion abnormalities persisted when patients were re-evaluated in the short-term period (mean 4.5 weeks). Longer term data is not available. 25,26

It is not clear whether patients who have a history of EVALI are at higher risk for severe complications from influenza or other respiratory viral infections if they are infected simultaneously or after recovering from lung injury. Healthcare providers should emphasize the importance of receiving the annual influenza vaccine for all people older than 6 months of age, including patients who have a history of EVALI. The pneumococcal vaccine also should be considered according to current guidelines. The long-term complications of vaping are poorly understood, and it is too soon to evaluate. Many of the carcinogens found in vaping products take years to decades to manifest.

Vaping Safety

Vaping often is used to replace cigarettes. Vaping is probably less harmful than smoking, but it still is unsafe.

E-cigarettes involve heating nicotine (extracted from tobacco), flavorings, and other chemicals to create a water vapor that is inhaled. Regular tobacco cigarettes contain 7,000 chemicals, many of which are toxic and cancerous.

Vaping contains dangerous chemicals, but it contains less than those found in smoking tobacco. Some of the chemicals found in e-cigarettes (nickel, cadmium, tin, lead, glycols, etc.) have been associated with cancer, and it seems logical that prolonged vaping will be associated with cancer(s).

Most e-cigarettes contain nicotine, which is highly addictive. Exposure to nicotine during adolescence can affect brain development, learning, memory, and attention.

Patients should be warned not to vape or smoke. If they persist vaping, they should not use THC-containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. They should avoid online dealers to obtain a vaping device and/or vaping liquids. (See Table 3.)

Table 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations |

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends not using e-cigarette, or vaping, products that contain tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The CDC also recommends that people should not:

Since the specific compound or ingredient causing lung injury is not yet known, the only way to assure that you are not at risk while the investigation continues is to consider refraining from use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. If people continue to use an e-cigarette, or vaping, product, they should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a healthcare provider immediately if they develop symptoms like those reported in this outbreak. Irrespective of the ongoing investigation:

The CDC will continue to update guidance, as appropriate, as new data emerge from this complex outbreak. If you have questions about the CDC’s investigation into the lung injuries associated with use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products, contact CDC-INFO or call 1-800-232-4636. |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

Continued Surveillance

Despite the epidemic waning somewhat, cases still are appearing, although in smaller numbers.

The CDC remains interested in obtaining the vaping solutions or products used by patients with EVALI. The CDC is offering aerosol emission testing of product samples from vaping or e-cigarette products and e-liquids associated with EVALI cases. Forms and directions for submission are found at www.cdc.gov.

The information also is available through the local poison control center. Analysis of the liquid will improve the FDA’s understanding of e-liquids and exposure among patients associated with the lung injury outbreak.

References

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future. May 20, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future

- Henry TS, Kanne JP, Kligerman SJ. Imaging of vaping-associated lung disease. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1486-1487.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Last reviewed Aug. 3, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

- Borodovsky JT, Lee DC, Crosier BS, et al. U.S. cannabis legalization and use of vaping and edible products among youth. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;177:299-306.

- Consumer Advocates for Smoke Free Alternatives Association. Historical timeline of vaping & electronic cigarettes. http://www.casaa.org/historical-timeline-of-electronic-cigarettes/

- Fortin J. This may be a first: Exploding vape pen ills a Florida man. The New York Times. Published May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/16/us/man-killed-vape-explosion.html

- Lee MS, Allen JG, Christiani DC. Endotoxin and (1→3)-β-D-glucan contamination in electronic cigarette products sold in the United States. Environ Health Perspect 2019;127:47008.

- Maddock SD, Cirulis MM, Callahan SJ, et al. Pulmonary lipid-laden macrophages and vaping. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1488-1489.

- New York State Department of Health. New York State Department of Health announces update on investigation into vaping-associated pulmonary illnesses. Sept. 5, 2019. https://www.health.ny.gov/press/releases/2019/2019-09-05_vaping.htm

- Moritz ED, Zapata LB, Lekiachvili A, et al. Update: Characteristics of patients in a national outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injuries — United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:985-989.

- Kalininskiy A, Bach CT, Nacca NE, et al. E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): Case series and diagnostic approach. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:1017-1026.

- Jatlaoui TC, Wiltz JL, Kabbani S, et al. Update: Interim guidance for health care providers for managing patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury — United States, November 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1081-1086.

- Agustin M, Yamamoto M, Cabrera F, Eusebio R. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage induced by vaping. Case Rep Pulmonol 2018;2018:9724530.

- Reidel B, Radicioni G, Clapp PW, et al. E-cigarette use causes a unique innate immune response in the lung, involving increased neutrophilic activation and altered mucin secretion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197:492-501.

- Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, et al. Notes from the field: Use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students — United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1276-1277.

- Chaumont M, van de Borne P, Bernard A, et al. Fourth generation e-cigarette vaping induces transient lung inflammation and gas exchange disturbances: Results from two randomized clinical trials. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2019;316:L705-L719.

- Westenberger BJ. Evaluation of e-cigarettes. St. Louis, MO: Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Division of Pharmaceutical Analysis. May 4, 2009.

- Bonilla A, Blair AJ, Alamro SM, et al. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraces and vaping in an 18-year-old man: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2019;13:283.

- Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin — Final report. N Engl J Med 2020;382:903-916.

- Chatham-Stephens K, Roguski K, Jang Y, et al. Characteristics of hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients in a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury — United States, November 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1076-1080.

- Siegel DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. Update: Interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury — United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:919-927.

- Sifat AE, Vaidya B, Kaisar MA, et al. Nicotine and electronic cigarette (E-Cig) exposure decreases brain glucose utilization in ischemic stroke.

J Neurochem 2018;147:204-221. - Davis DR, Fucito LM, Kong G, et al. Adapting research protocols in response to e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): A response to CDC recommendations for e-cigarette trials. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:619-620.

- Mikosz CA, Danielson M, Anderson KN, et al. Characteristics of patients experiencing rehospitalization or death after hospital discharge in a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;68:1183-1188.

- Carroll BJ, Kim M, Hemyari A, et al. Impaired lung function following e-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury in the first cohort of hospitalized adolescents. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;55:1712-1718.

- Reddy A, Jenssen BP, Chidambaram A, et al. Characterizing e-cigarette vaping-associated lung injury in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Pulmonol 2021;56:162-170.